Servitization is a business model in which a machine (i.e., forklift, truck, order picking robot) is not sold, but is accessed by an end-user through a multi-year fixed-fee outcome-based service-contract. A servitization contract can be attached at the time of the delivery of a new or used machine, as well as engaged anytime during the post-delivery of a machine.

The service typically encompasses the following 15 elements:

1. The equivalent of an operating lease is supplied; machine ownership is never transferred to the service recipient. Many of these machines in the future will be autonomous.

2. The intellectual property (IP) of a machine’s embedded software configuration is not controlled by the service recipient, but by the owner of the machine.

3. Solutions are supplied to maintain (i.e., break/fix) and improve (i.e., upgrade) a machine’s capability (i.e., lift 5,000 pounds), employability (i.e., 95% uptime in a 24-hour period) and deliverability (i.e., 8 hours of operation per day).

4. An outcome-based fixed-fee is typically aligned with the customer’s revenue streams; in fact, the fee becomes a variable cost. For example, a public warehouse forklift user could be charged a fee of $3.75/ton for movements from storage to staging and loading of a vehicle; the fee would be directly aligned with their handling charge of $4.50/ton for the same movements to its customers.

5. Solutions are delivered for a continuous period of time during the post-production lifecycle of a machine; when over 1 year, revenue recognition financial reporting is required.

6. The performance levels of solutions delivered are assured. For example, technicians will arrive on-site for a break/fix event within two hours of being notified within any 24/7 period.

7. Amendments are incorporated to the contract, such as up-selling or cross-selling; will often occur as a result of changes in the business environment of the customer during the multi-year contract duration.

8. Contract renewal is aggressively pursued; it is a major end-game of the business model.

9. A supplemental fee schedule is established, for solutions delivered that are not supported in the contract.

10. Guidance for the price and configuration for quotes of the pre-landed contract is overseen by one entity (i.e., Obligor).

11. Higher profitability for seller; typically 25-150% higher than that of a product.

12. “Stickiness” of buyer-seller relationships; continuous contact for years.

13. Higher sales commissions for account managers; multi-years’ worth of booked sales.

14. Optimized budgeting for buyer; converts CapEx to OpEx and reduces number of transactions.

15. One “button to push” by buyer to address any performance issue with seller.

Currently, the decade-plus employment of the term of “servitization” has primarily been the focus of European Union-based academia and EU OEM Board of Directors (BOD) suites. In the last 2-3 years, EU-based OEMs have been touting the term in their U.S.-based operations. Also a limited group of U.S.-based academics and management consultants have been discussing the model as well.

As of today, few U.S.-based BODs or investors are familiar with the term, but it is my belief that will be changing in the near-term. Note that the terminology employed for the U.S.-based business model may be different than that of the EU-based “servitization”; currently U.S.-based firms employ terms such as “subscription” and “Product-as-a-Service (PaaS)” that encompass many of the elements of “servitization.”

A New Business Model

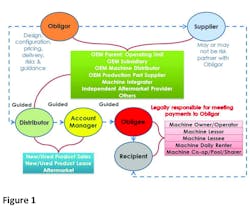

For a new business model to succeed all the actors engaged in the model must have a self-interest in its embracement. Below are the six actors who will need to sign-on to the model (see Figure 1).

Obligor

Designs, configures, engages suppliers employed in the delivery of solutions (i.e., machine, technicians, repair shops), selects sales channel, prices, guides selling options, manages financial/operational risks, and oversees the performance, amendments and renewal of the contract (i.e., OEM, OEM subsidiary, OEM distributor, OEM production subsystem supplier).

Supplier

Provides resources, selected by the Obligor, for delivering the solutions (i.e., OEM aftermarket unit, OEM distributor, third-party independent).

Sales Channel

Group of enterprises that engage in relationships with buyers demanding a like-kind product and/or service (i.e., OEM, OEM new product distributor, manufacturing representative).

Account Manager

Engaged in the sales process of configuring and delivering a guided quote to a buyer (i.e., new product sales person, aftermarket sales person).

Obligee

Entity that signs contract and is obligated to meet its terms & conditions [T&C] (i.e., corporate fleet manager, cooperative, machine site manager).

Recipient

Touch-point of the supplier delivery the solution (i.e., machine operator, machine maintainer).

Note that one entity can be concurrently several actors in the business model. For example, an OEM can be: the Obligor, the in-house Supplier of resources for the delivery of solutions, the Sales Channel organization in which it sells directly to the Obligee, and finally the employer of the Account Manager

The "Magic Sauce"

Now that we have defined the actors, let us identify the self-interest of the actors in embracing servitization or its like-kind business model. Note that as in any business model, there is always the risk of losses, but there is also always the ability to generate significant profits from effectively and efficiently delivering a service demanded by potential buyers.

In one perspective, the revenues generated from servitization simply shifts transactional-based revenues to that of the contract. For example, a preventive maintenance (PM) task is scheduled every 600 hours employing $1,000 of parts; this will be done either by the maintainer/owner purchasing $1,000 of parts in a transaction or having the parts bundled in the contract’s pricing of the fixed-fee per hour of operation. At this point there is little incentive for the actors to embrace servitization; it appears to be a zero-sum game.

But now we begin the discussion on the “magic sauce” of servitization. There are five major drivers for the actors to embrace this model. As noted previously, some of the actors may be affiliated with the same enterprise.

Higher Profitability

● For Obligor: Continuing our previous example, the Obligor, as a result of a fixed-fee per hour of operation, has a powerful incentive to reduce parts demand per hour of operation. The Obligor has various paths to pursue in order to reduce the frequency of PM tasks, and in turn reduce costs and improve profits over the life of the contract; from improving the reliability of the part through a modification, to improving the manufacturing quality of a replaced part. To continue with our example, if the Obligor was to reduce the PM frequency from 600 hours to 900, and the contract was for 3 years or 1,800 hours of operation, the cost of parts employed would decrease from $3,000 to $2,000. If profit margins were originally 20% on each $1,000 part, the planned profit over the life of the contract would have been $600 (i.e., 3 removals at 20% of $1,000), but with the aforementioned change in PM, the profit would be $1,400 (i.e., 2 removals at 20% of $1,000 and $1,000 saved) or a 130% increase in profitability. Of course the other side of the coin is that if the PM frequency declines from 600 hours to 300 hours, the Obligor would incur a major loss.

● For Supplier. In order for the Supplier to also benefit in the above, they must be legally aligned with the profit improvement initiatives of the Obligor; typically achieved through an arrangement that shares in the profits such as a Limited Liability Corporation (LLC).

Contracted Recurring Revenues

● For Obligor & Supplier. The investor community is “excited” about such a recurring revenue business model; they reward the enterprise with highly favorable valuations that can exceed the price/earnings (P/E) ratios of their peers by 25%-50%. Future revenues, and their profit, are reflected on the balance sheet of the Obligor or the Supplier as a long-term contracted service asset.

“Stickiness” of Relationships

● For Obligor. Engaged in a long-term relationship between the Obligee and the Recipient, providing opportunities for future renewal revenue opportunities.

● For Obligee and Recipient. “Peace of mind” of “having their back” as to machine outcomes meeting their business needs. Also converting some Capital Expenditures [CapEx] into Operating Expenses [OpEx]; reduces certain budgeting challenges, as well as the administrative costs of a transaction-based relationship.

Sales Commissions

● For Sales Channel and Account Manager. Though extra effort is typically required to “seal a deal,” the commissions can be materially larger than that of transaction-based sales of products and services. Also additional revenue opportunities can arise as a result of recapturing their share of the aftermarket that they had previously lost.

Optimized Performance of Machine Models

● For Obligee and Recipient. In order to meet outcome performance assurances, the Obligor will provide the Obligee and the Recipient with continuous improvement in the capabilities, employability and deliverability of the machine.

● For Obligor and Supplier. As a result of continuous pressure to improve machine performance in order to optimize profits, as well as Obligee and Recipient relationships, product design changes will be identified and embraced; a “free” source of input for R&D of a machine model.

Not If But When

Below are some of the factors that may hinder the embracement of servitization by the material handling and logistics community:

1. The difficulty in changing organizational cultures of actors.

2. The potential risks of large multi-year losses for Obligor.

3. Challenges of Obligor and Suppliers in educating the investor community of the new business model on the income statement and balance sheet.

In conclusion, it is not a matter of if the “servitization” business model will be embraced by the MH&L community, but when. It will be a difficult journey, of 10-25 years, but when early adopters demonstrate the financial and relationship benefits, the rest of the community will follow suit.

Ron Giuntini is principal of Giuntini and Company, president of G35 Software Inc. and a member of the MH&L Editorial Advisory Board.