It's often said—by professionals and academics alike—that decisions surrounding the best business relationship strategies come down to getting the math right. This is especially true for outsourcing, re-shoring, near-shoring, next-shoring and off-shoring—misunderstood terms that frequently make it all pretty confusing. It doesn't have to be that way.

That's because many companies focus mainly on manufacturing, pricing and labor costs. That focus needs to be expanded to the Best Value and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

Before getting into these concepts, let's make something clear: outsourcing and off-shoring are not interchangeable terms. Outsourcing does not automatically mean that jobs are lost to another country. When a company sources its production facilities offshore—in China for example—it is probably focused almost exclusively on price and cheap labor. This is not the same as outsourcing a company's non-core functions—payroll for example (which might occur across the street)—in order to concentrate on its core functions. Thus a decision to "re-shore" or "near-shore" is not a slap at the outsourcing concept in general. It has much more to do with acknowledging that the original decision to offshore was perhaps a miscalculation, or that economic conditions have changed. The latter point is especially germane as companies continue to adjust to the post-financial crisis. Outsourcing is not offshoring, it is about best-shoring, and near-shoring is becoming an important element of the outsourcing arsenal as we adjust to new economic and financial global conditions.

Best Value and TCO

It's well past time to shift the business relationship mindset from price to value – creating, sharing and expanding the value of the business enterprise. The University of Tennessee and Sourcing Interests Group's "Unpacking Best Value" white paper says progressive companies are challenging conventional approaches, realizing it is not how much they pay, but how much they get. That's the Best Value mentality.

Best Value takes procurement professionals out of the price-only focus so that they understand the total cost of the deal or enterprise in front of them. This is TCO. Best Value and TCO go hand-in-hand, and when understood and implemented properly, pricing becomes value-based and becomes a win-win.

Put simply, it's not about how much you pay, it's about how much you get. In a nutshell, that is the basic difference and tension between price and value. Best Value approaches become the bridge spanning that tension because determining the true cost and value equation translates into confidence that companies are getting the best deal.

Low-Bid Problems

Sticking solely with low-bid contracts does not necessarily generate savings. Ever hear of cost and time overruns? If you've followed the news about the Panama Canal's contractors' $1.6 billion construction shortfall—which threatened the completion of the project—you know about the dangers of the low-bid contract.

Many organizations with low-bid policies in place will often fail to do the due diligence needed to study what went into the bid "price." They fail to determine the total costs of ownership or do a Best Value analysis because they are blinded by the low number on the page. Not seeing the total picture can lead to disaster.

That's why Best Value approaches, tools and methods—such as TCO—are gaining traction. Even government agencies that traditionally relied on competitively bid "lowest price" policies have started to deploy Best Value concepts.

In 2001, the state of Minnesota enacted a law that put discretion into the bidding process. The Minnesota Department of Transportation then used the new law to select the contractor to build the I-35 St. Anthony Falls bridge replacement after its collapse in 2009. Why? It enabled the agency to balance cost, quality, incentives and timeliness as the key factors in choosing the contractors that would do the bridge construction. The result? It selected the contractor with the highest price, but the overall Best Value. It became one of the most successful bridge construction projects in history, erected in a staggeringly short time period (less than 18 months), and it eventually won many awards. (See the Vested case study, "Vested for Success: Minnesota Turns 1-35 Bridge Tragedy into Triumph.")

Calculating Value

The advantage of using the TCO model is that businesses can make clear, informed decisions when it comes to price and value decisions, and when and where to outsource.

The researchers Jaconelli and Sheffield describe the intent of Best Value as enabling a balance between cost and quality considerations, while ensuring ongoing value for money and promoting continuous improvement to further value for money.

Consider Best Value an equation that balances decision criteria among alternatives; a simple calculation provides a visual representation of how to calculate Best Value:

Best Value = Optimum Benefit

(sum of criteria as defined by the buyer)

– Buyer's Total Costs

Documenting the entire picture by capturing the costs of the buyer and the supplier is the only way to get to the actual total costs. This includes all cross-departmental costs within the buyer's organization as well.

Cost Analysis

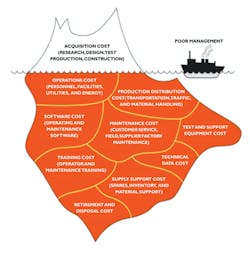

A baseline TCO analysis includes the costs under current conditions as well as projections based on a set of assumptions. The preferred approach is always transparency, where the total costs to own a product or use a service over time is factored into the price. Some of the most common items to include in a TCO analysis include:

- Design and development costs

- Hard costs (e.g., labor and assets)

- Operating costs (e.g., energy and maintenance)

- Soft costs (e.g., overhead, corporate allocations, training)

- Installation and commissioning costs

- Governance costs (e.g., cost to manage the relationship)

- Software costs

- Supply chain support costs

- Retirement, disposal costs or residual value

- Opportunity costs, including reduced downtime, increased production yield, or sales value or increased sales or margin for developing a better product

- Transaction costs, including cost of switching suppliers and costs associated with a competitive bid and contracting process

- Environmental or sustainability costs or savings

Identifying all the true total costs is not so straightforward, however, and it is often not easy. Drilling down to the "hidden" or below-the-surface costs is crucial because those hidden costs can comprise about 80 percent of total costs. The Priceberg shows the importance of looking at the hidden costs.

Understanding only the price—the number above the waterline—is like seeing only the tip of the iceberg. The parties in the deal could get that sinking feeling, because what is out of sight can cause the greatest damage.

With transparency, collaboration and an atmosphere of growing trust, which is the Vested model, a proper pricing mentality and the Best Value for the long-term viability of the enterprise – whether it's outsourced, offshored or re-shored – will fall into place.

Kate Vitasek ([email protected]) is a faculty member of the University of Tennessee's Center for Executive Education. She is also the principal author of The Vested Way: How a "What's in it for We" Mindset Revolutionizes Business Relationships.