The U.S. military operates in many places around the globe, defending the homeland from attack. Where logistics is concerned, however, their missions require different approaches.

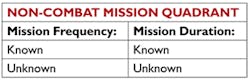

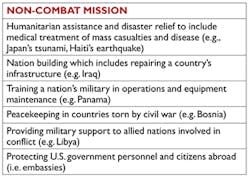

The non-combat missions engaged by the military are listed below and fall into one or several of the quadrants above.

The U.S. military has become the world's benchmark organization in delivering logistics solutions for non-combat missions whose frequency and duration are unknown. These are primarily its humanitarian assistance and disaster relief missions. The mission-enterprise is a virtual organization, with a small oversight staff, whose objective is to ensure that when a mission event occurs, logistics processes have been defined to enable the military to assemble and disassemble the temporary mission-enterprise within desired timeframes. These processes include identifying, acquiring, maintaining, controlling, issuing, retrieving and redistributing supplies.

Resources (people, facilities, equipment, materials, and data/imagery/voice files) to be employed in each logistics process must also be defined, as do the suppliers of these resources. That definition includes what must be done organically by the military, by contractors and by the host country. The effectiveness of these resources will have to be validated through training exercises.

Logistics to the Rescue

Let's see how the mission-enterprise is exercised in the real world by reviewing the devastating tsunami of December 26, 2004.This horrific event affected eleven countries, leaving hundreds of thousands dead and homeless. On December 28 the U.S. Pacific Command based in Hawaii formed Joint Task Force 536, later named Combined Support Force 536, and gave it the mission of providing immediate and sustained relief to the region. The relief operation was named Operation Unified Assistance.

While the assessment of military capability necessary for relief operations was underway on December 29, initial relief materials were already being delivered to those countries hardest hit by the resulting floods. Control and visibility of units and materials flowing into the region were emphasized in order to ensure useless assets did not enter the pipeline.

While the U.S. military was one of many participants, its role was one of rapid response to provide initial relief while other organizations and countries organized their assets for the overall relief effort. Immediate relief of suffering was paramount. This mission orientation was a key planning tenet.

Rapid response planning to known and unknown missions is practiced by all services to ensure each is able to provide immediate response to a crisis. A logistics needs assessment ensures provision of the right stuff, at the right time, at the right location. The needs assessment directly measures what is required in the affected area covering the range of functional areas: engineering construction, utilities, medical, food, water, transportation, distribution, coordination, and security.

The military's forward presence in the region plus the comprehensive logistics capacity it possesses made it the most effective initial reaction force. A unique nuance of this relief effort was that the political climate of each nation dictated particular requirements for disaster relief as well as coordination with United Nations organizations.

Assets of Unified Assistance

The combined assets of each of the U.S. military services in the region resulted in a massive logistics capacity available for relief efforts within 7 days. Assets employed in the region included:

- 17 Navy ships, to include an aircraft carrier and a Coast Guard cutter;

- Maritime prepositioned ships loaded with supplies to include food, medical and construction materials;

- USNS Mercy, a floating trauma center with the capacity to house up to 1,000 hospitalized patients. Mercy's personnel conducted a wide range of medical and dental assistance programs ashore and afloat, performing 19,512 medical procedures, including 285 surgeries;

- USS Fort McHenry, a dock landing ship that left Sasebo, Japan, Jan. 2, delivered more than 1.2 million pounds of water, food items and clothes;

- Hundreds of Marine Corps engineers and Navy Seabees helped Sri Lankans repair infrastructure and clear debris;

- Army engineers deployed to Thailand to help rebuild roads, bridges and power infrastructure;

- Over 70 reconnaissance flights assessed damage, resulting in roughly 570 hours flying time;

- More than 1,300 fixed-wing aircraft flights resulted in more than 4,635 hours of flying time;

- More than 2,200 helicopter flights resulted in more than 4,870 hours of flying time.

equipment into the region by Feb. 14, when Combined Support Force 536 ceased operations.

Because of the massive coordination effort required between the military and civilian agencies, the Combined Support Force units actually relied primarily on cell phones and e-mail for much of its connectivity and communications. Coordination of aircraft and ships still required the use of military communications channels.

Lessons Learned

Not everything went as planned. Much of the supplies being directed to the region were “pushed,” resulting in pockets of mal-distribution. But the DoD got the job done and saved hundreds of thousands of victims from even further misery.

The last piece of the logistic challenge from this mission was what is referred to as “reset;” a process that returns deployed equipment back to its original condition. This one-off mission created an Operational Tempo [OPTEMPO] that was not sustainable for a long period of time. It would be like an over-the-road truck running 24/7 for weeks; you know that if it wasn't brought back to a maintenance facility sooner, rather than later, downtime and safety issues would surface. And that in fact occurred with much of the equipment employed; it took months of some serious maintenance work to get all returning equipment in a condition that would enable our military to engage in future combat or non-combat missions.

In Conclusion

The U.S. military's logistics capacity to provide food, water, medical and utilities and the capability to move into almost any region of the world is second to none. Flexible and robust, it can tackle many missions other than direct combat. Planning for such events is part of its curriculum.

Elaborate facilities are not required. Whether based at sea or in an austere land environment, the services can operate in disaster stricken environments, bringing initial relief to those who are suffering. The pipeline back to the U.S. keeps replenishment moving to units distributing it. The U.S. military is truly a “911 force” when tragedy strikes.

Alan Will is a retired Marine colonel and logistics specialist. Ron Giuntini is a consultant and principal of Giuntini & Co., Inc. Both are members of MH&L's Editorial Advisory Board.